Advanced example¶

In this section, we detail a more complex example of a TFC use case. In this example, we don’t have any default network and we publish only partially on the available networks.

We also introduce some advanced annotations such as @POPPrivate that can be used in more complex applications, and new parameters such as localhost, tracking and localJVM.

@POPClass

public static class A {

private int n;

public A() { }

@POPObjectDescription(url = "localhost", protocols = "ssl",

tracking = true, localJVM = true)

public A(int n) {

this.n = n;

}

@POPSyncSeq

public int get() {

return n;

}

@POPAsyncMutex(localhost = true)

public void set(int n) {

this.n = n;

}

@POPSyncSeq

@POPPrivate

public void divide() {

n /= 2;

}

}

This class does the same as the one in the preceding example: it exposes a value to whoever wants to know it, except that now we have the possibility to modify the value even after the object creation. However, this feature is not for everyone!

Local JVM objects¶

We can see in the @POPObjectDescription annotation that we have two new attributes:

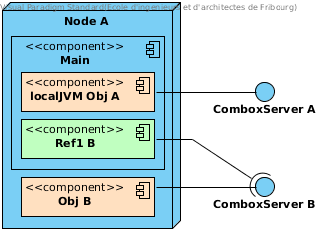

tracking, which allows to know who used the object;localJVM, which allows to integrate the object in the current JVM instead of spawning a new one (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Main create two POP objects: the first is a localJVM and the second a classic JVM.

Why creating an object this way? There are multiple reasons, the main one being that a POP object spawned locally does not require the data to be transmitted via a Combox and has access to all non-POP objects created in the JVM. This notably permits to make data accessed from a non-POP platform available to a POP application.

That said, this not an all in one solution: localJVM should be used with care! The annotations used to achieve synchronicity may not work (particularly async), unless we treat the object as if it were remote.

A al = new A(10); // local JVM

A ar = PopJava.getThis(al); // connect to the local JVM object

In the example above al is a localJVM object and is treated as such. ar also points to the same object al but must pass through a Combox to make calls. Thus, it also loses access to some methods.

Local special access method¶

localJVM is generally used to make a hybrid application working with non-POP objects. Thus, some object methods might not be available for every connecting client but only for the JVM which created the object itself.

The @POPPrivate annotation is meant for keeping a method accessible to the JVM which created the object and not exposing it remotely.

// Node A

A local = new A(10); // local JVM

A ref1 = PopJava.getThis(local); // Connect to the local JVM object

// Node B

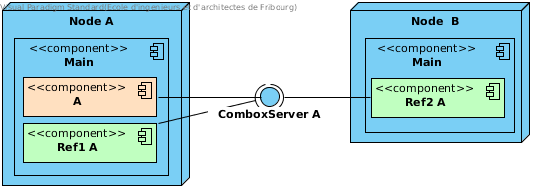

A ref2 = PopJava.connect(...) // Connect to nodeA -> local remotely

In the code above, we create a localJVM object and connect to it by creating a reference. Then we have a remote machine which is also connected to it. Figure Figure 2 shows the situation.

Figure 2: Local JVM with local and remote connections

In this local example, we can call the method divide; ref1 and ref2 do not have this method exposed because it is annotated with @POPPrivate.

Remote special access method¶

@POPPrivate is not the only restriction that we can make. The set method has an attribute in its annotation: localhost = true. This attribute automatically checks that the calls to this method come from someone on the same machine than the object.

In the same preceding example, we can see that the set method is not accessible by everyone, but only by objects on Node A. Table below shows the access to the three methods of A.

| Method | local | ref1 | ref2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| get | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| set | ✔ | ✔ | ✖ |

| divide | ✔ | ✖ | ✖ |

Tracking¶

Tracking allows to know how long an object was used and by who. Calls to a specific API with a POP object as a target permit to obtain this information.

Let’s take the same example used in the two previous chapters: one object receives two connections from two different sources and is also used locally.

Note

It’s important to know that we can not track the usage of a localJVM object, unless we are connected to it via a Combox. This means that we will never know how local uses A.

The person who created the POP object has access to its usage statistics. In fact, only the owner of the object knows all the users who used it.

The following information is usually extracted from a connecting user: the certificate (if present) used to identify the user, the IP address and the network used for the connection.

Note

POP-Java does not handle the real identification of a user. It’s the job of the one creating an application to provide this ability.

- To access the statistics of a POP object, we use the API provided by the class

POPAccounting, which can do 3 main things: - Check if an object has tracking enabled

- Retrieve the users which used the object

- Ask the statistics of a given user

- Ask the statistics of a current connection

Own statistics¶

Accessing your own statistics can be useful to check how much you used another person’s‘ shared object before closing a connection. The usage is stacked and connection independent, meaning that the statistics cumulate and are not reset between two connections to an object.

POPTracking own = POPAccounting.getMyInformation(a);

POPTracking contains information that the owner of the object can see about you, in order to identify you and see your usage of the methods in the object.

Object statistics¶

As the owner of an object, you may be interested in knowing who used your object. To do that, you first need to request a list of users of the object. Then you can successively ask detailed information about each user.

POPRemoteCaller[] users = POPAccounting.getUsers(a);

for (POPRemoteCaller user : users) {

POPTracking info = POPAccounting.getInformation(a, user);

// do something

}

Tracked information¶

- We generally track three things done by the user:

- the methods he used;

- the number of times he called each method;

- the duration of the method execution (usage);

- the size of the method input data;

- the size of the method output data.

With those information, the owner of an object can gather enough information e.g. to fill in an invoice.